November marks Bereaved Siblings Month – a time dedicated to acknowledging the unique pain and sorrow experienced by siblings who lose a brother or sister. Losing a sibling is an incredibly challenging experience, and this month aims to create awareness, support and resources for bereaved siblings to cope with their grief.

Road crashes shatter lives and families, leaving behind a trail of devastation. While much attention is rightfully given to parents and other immediate family members, the grief of siblings often remains in the shadows.

Bereaved Siblings Month provides a platform to address the specific challenges faced by brothers and sisters who lose their siblings in road collisions. In much the same way, the RoadPeace Bereaved Siblings Support Group provides a lifeline for individuals coping with the profound loss of a sibling in a road crash. The online support sessions offer bereaved siblings of any age the opportunity to meet others who have suffered a similar traumatic loss and provide one another with mutual support.

Later this month, it will be nine years since our Bereaved Siblings Support Group Co-ordinator, Lucy Harrison, learned that her brother, Peter, had been killed by a speeding hit-and-run driver.

In this heartfelt blog, she tells us how Peter’s death shattered her world and how, thanks to the support she received, she has learned to smile again.

By Lucy Harrison

The 29th November will mark the ninth anniversary of my brother, Peter’s, death. In many ways, it is hard to believe nine years have passed since I woke early on a Sunday morning to that doom-filled door knock. I can vividly recall the look on my dad’s face as he broke the news that Peter had been killed by a speeding, hit-and-run driver. Even now, the thought of this makes a feeling of fear take over my body. On the other hand, the idea that nine whole years have passed since I heard my brother laugh, saw his name pop up on a text message notification, or sought his unique advice, causes actual physical heartache.

Don’t get me wrong – life is good now. There were times I genuinely never thought I’d be able to say that – but it is. I have an amazingly supportive network around me (largely thanks to the RoadPeace West Midlands and West Mercia groups which I am privileged to coordinate). I have learned to laugh again and feel it. I have learned to smile again and mean it. Yet, the sadness still co-exists alongside those moments of joy. To an extent, it has taken me this length of time to really understand the impact of Peter’s death, and accept that this will be with me forever.

This is why I was so thankful when RoadPeace agreed to let me coordinate a new national support group for bereaved siblings. It’s not that I think losing a sibling is any worse or any easier than losing any other loved one in a road crash – every relationship matters, every relationship is different. Each of us bereaved through a road crash hurt deeply and desperately. Yet, to have a space to talk specifically about the sibling relationship has been a comfort. The other bereaved siblings who attend have helped me to finally acknowledge sibling loss – something which isn’t widely talked about.

Forgotten mourners

The phrase ‘forgotten mourners’ is sometimes used for bereaved siblings. In a way, this can feel a bit unfair, but there is some truth to it. It’s not as though people forgot that I was grieving for my brother – and I would be doing my family and friends an injustice if I didn’t acknowledge how much they tried to help. It’s just that sometimes, the way society responded to me, as a grieving sister, was different.

Looking back, it was rare that anyone would directly address the subject of Peter’s death with me. Sometimes my grief felt like some kind of dirty laundry – people knew I was going through it but they didn’t want to mention it. However, those that were brave enough to broach the subject inevitably enquired how my parents were, or how Peter’s partner was. I’m sure they didn’t mean it in this way, but that left me with a sense that as a sibling, my grief was somehow less valid than everyone else’s.

I hadn’t lived with my brother for many years, so unlike his partner, I wasn’t having to get up each morning and look at his things, think about how I would pay bills without his income, or adjust to coming back to an empty house. I hadn’t assumed I would die before my brother (I’d never really thought about this), so unlike my parents, I wasn’t finding money to pay for an unexpected funeral that felt completely out of the natural order of life. I returned to work after less than a week off. My brother’s partner was signed off sick, and my dad was retired – but somehow there was an assumption from everyone (including myself) that I had no reason to not work. I used holiday to be able to attend the court hearings that followed (holiday, really).

I started to feel like my role was to grow up, and think of everyone else – that my own pain somehow needed to drop down the list of priorities, because it couldn’t possibly be as deep as that of others. I’m not sure anyone else really thought my pain was less – but nobody came forward to ask me how I was doing having lost a person who’d been in my life since the day I was born.

Yet, I was hurting. Big time.

A new identity

Without realising it, many of us place so much of who we are on where in the family we fall. It might be you are the oldest, the middle child, the baby, a big brother, or a little sister. I had gone through life with two big brothers, twelve and ten years older than me. I was quiet and thoughtful, often looking up to my oldest brother who was loud and outgoing. Peter supported Birmingham City Football Club, so I did. Peter loved going to the horse races, so I did. We shared the same the same relatives, the same childhood and many of the same memories. Without ever really needing to discuss it, we understood many of each other’s traits, reactions and outlook on life – because we were shaped growing up in the same house.

Suddenly, this huge connection was gone.

I remember being at work one day and overhearing someone say, “That’s the girl whose brother was killed.” It felt like being punched hard in the stomach – my brother had died, and in a way my place as the baby in the family, the little sister, had too. I started to get anxiety around meeting new people, whether professionally or socially. After all, a common question when you are getting to know someone is, “How many brothers and sisters do you have?” Nine years on, I can still stumble over this question – feeling both sick and silly that I don’t know what to say.

If I tell someone I have two brothers, they might go on to ask me what they do or where they live – so I have to explain what happened. I can’t say I have one brother – because for me, this would feel like I was erasing Peter. Sometimes, I might say I have two brothers but sadly, one has died – this will inevitably lead to more questions which I don’t really want someone I have just met to ask me. It’s a straightforward and perfectly normal question, but I dread it. If any other bereaved siblings have a way of coping with this – please tell me.

Of course, I was, am, and always will be, Peter’s little sister. My big brother has left memories that will fill my heart and mind for all time. However, it’s a fact to say I had to grow up overnight and assume a different place within my family. My other brother has learning difficulties – this means the support he can provide to me is limited. One day, and I hope it is a very long time from now, I am likely to face further losses – and I won’t have my big brother to share that grief with me, in a way that only a sibling could. If I am lucky enough to live to be an old lady, my brother won’t be there as a living connection to the past. Will I feel lonely? I don’t know.

I do know that due to Peter’s death, there are so many fears and vulnerabilities I never expected to have to face. Before the siblings’ group, I was afraid to discuss these – but now I am finding the strength to say them out loud.

Living for my sibling – the guilt

I was wracked with guilt following my brother’s death. I’d find myself having what I can now see were irrational thoughts – but at the time they felt very rational. I thought that if one of the three of us had to be taken – then it had happened to the wrong one. My mind would go down a rabbit hole; convinced that my brother would have coped better, had more of an idea of how to support my parents, or made more sense of the criminal justice system than I could. I felt like a bad sister. I felt I was letting him down. This led to all kinds of issues, dramatic weight loss, withdrawing from friends, extreme exercise. I sometimes tried to explain just the surface of these feelings to friends, but they’d tell me I needed to go to the doctor, or that I needed to move on. Until I found RoadPeace, nobody was telling me it was okay to hurt like hell and go through every kind of emotion because I’d lost my brother. I needed someone to actually tell me this – that grieving for a sibling was perfectly acceptable.

I would channel a lot of this guilt in trying to live for Peter. I tried to do things my brother liked – I went to Warwick races but it broke my heart, because it just wasn’t the same without him. I started campaigning with my friend, putting everything into trying to make changes in Peter’s memory – and I am glad we did this, but I burnt out. I tried to visit my other brother as much as I could, somehow hoping to fill the hole Peter had left, but that was impossible. I threw myself into my job because Peter had always been such a hard-worker, I thought he would have approved of that, but my job no longer fulfilled me.

I didn’t know what I wanted to do for me anymore, I didn’t think I deserved hopes or dreams or to plan for a future. Again, this is something all those I have met through RoadPeace (not only the siblings) have helped me to overcome – a dangerous driver robbed my brother of his life, I couldn’t allow that driver to rob me of my life too. Sometimes, these feelings do resurface. Three years from now, I will be the same age as my big brother, four years from now, I will have outlived him. This haunts me. But, I know with the help of the other bereaved siblings in RoadPeace, I will talk it through, and make it through.

More than this, I know my brother would want me to be happy. It won’t ever be the same kind of happy I knew before his death, it will be a different kind of happy – but the last thing he would want is for his little sister to torture herself.

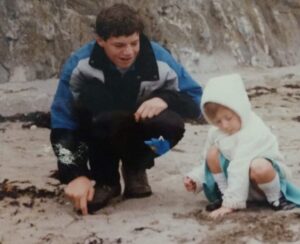

Lucy and her big brother, Peter

Lucy and her big brother, Peter

Accepting a different future

So, I guess it all comes down to the fact that with Peter’s death there came a point I had to accept my future had changed. That is the harsh reality. This is no different to any other bereavement – a parent, a partner, a child, a friend. The world might not stop, but grief stops your world. My point is, it may not seem so obvious that it feels like this for a sibling too – even an adult sibling who may not have had daily contact with their brother or sister for years.

I don’t like to go too far from my parents now – I worry about them; family has become a primary consideration for me in every decision I make – where to holiday, or what job to take. I don’t have a sibling who can help, so I feel this responsibility solely. My parents worry about me; anywhere I go, they want to know that I have reached my destination safely, they were never quite this protective before. There is nobody that can advise me in the way Peter could, because there is nobody else that will ever understand who I am and where I come from, in the way he could. Nobody else will ever protect me, while equally encourage me to have fun, in the way my big brother did. I won’t be an auntie, and if I ever have children – while I would always tell them about their uncle, it won’t be the same. My career changed – I ended up working for RoadPeace and becoming a local councillor – all as a result of the outrage I felt following my brother’s death. If Peter hadn’t been killed that night, my life would look very different.

My daily routine didn’t change, neither did the place I lived or my economic situation – and, thank goodness this was the case. I can’t imagine what it must be like to lose a partner, parent, or child, and the unique challenges these losses would bring. It must be awful. Grief is awful full stop. Grieving someone who has died in a road traffic collision, violently, and with no warning, is an extra layer of awful.

We need to be given the space to talk honestly about this – and this is why RoadPeace’s peer support is so important. Society needs to stop shutting down bereavement as too awkward a subject, and those who have been lucky enough not to experience loss yet, need to realise people often want to talk about their loved ones…and as part of this, we need to talk more about sibling loss.

With Peter, I lost a person who both connected me to my past and was supposed to be beside me in my future – and thanks to the other bereaved siblings I have met, I finally feel able to share this – and that is a relief.

The next group for bereaved siblings will be held on zoom on Saturday 25th November, at 10am. If you are interested in attending the group, please email the RoadPeace helpline at helpline@roadpeace.org.

November is a significant month for bereaved people. World Day of Remembrance will take place on Sunday November 19, 2023, to remember the many millions of people who have been killed and seriously injured on the world’s roads and to acknowledge the suffering of all affected victims, families and communities. Find out more here.

Updated on: 1 November 2023